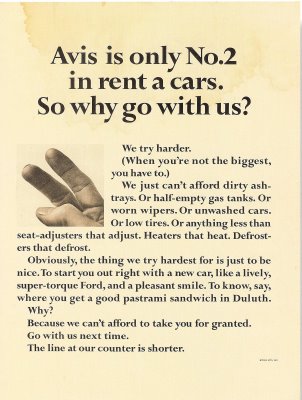

In the 1960s, Avis Rent-a-Car famously coined the slogan “Avis is only No.2 in rent a cars. So we try harder,” and unleashed a campaign to tout how their runner-up status meant they would work harder to win the hearts of customers.

The ad campaign has become legendary in the marketing world, but it turns out being #2 also has a shadowy side, as found by social psychologists who studied the reactions of silver and bronze medalists in the 1992 Summer Olympics (click here to see the PDF article from the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology). While the study measured several outcomes, the basic finding was this: Silver medalists were most pre-occupied with the shortcomings of their performances and what they didn’t achieve, while bronze medalists found themselves in a profound place of gratitude for making it to the podium. In the end, athletes who are #3 find themselves visibly more happy (as demonstrated by facial expressions and interview feedback) than the second-place finishers.

In the 1960s, Avis Rent-a-Car famously coined the slogan “Avis is only No.2 in rent a cars. So we try harder,” and unleashed a campaign to tout how their runner-up status meant they would work harder to win the hearts of customers.

The ad campaign has become legendary in the marketing world, but it turns out being #2 also has a shadowy side, as found by social psychologists who studied the reactions of silver and bronze medalists in the 1992 Summer Olympics (click here to see the PDF article from the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology). While the study measured several outcomes, the basic finding was this: Silver medalists were most pre-occupied with the shortcomings of their performances and what they didn’t achieve, while bronze medalists found themselves in a profound place of gratitude for making it to the podium. In the end, athletes who are #3 find themselves visibly more happy (as demonstrated by facial expressions and interview feedback) than the second-place finishers.

When I heard about this study today on NPR during a piece about the Sochi games, I was instantly intrigued. As a former social psychologist (my primary focus during short-lived doctoral studies prior to my foray into food), I just love the creativity that went into this study and the profound light it sheds into our preponderance towards “counterfactual thinking,” i.e., getting fixated on what “might have been.”

As a Buddhist practitioner and student/teacher of meditation, I think the findings of this study make an emphatic case for why gratitude is such an essential practice for finding contentment, whether in athletic competition or any other arena of life. It also makes the case for why working to tame the comparing mind is an essential part of any sincere spiritual practice.

In spiritual circles, we would call counterfactual thinking something like “not being in the present moment”. Call it what you like, we give a lot of energy to it, ruminating about the past and outcomes that didn’t go our way or “should have” gone another way.

In my personal experience, the strongest antidote to counterfactual thinking is gratitude. When we practice gratitude, we have no choice but to abandon our notions of what might have been in favor of finding the jewel amongst what is. Instead of fretting over the person who never called us for a second date, we remember what we appreciated about the first date. Rather than obsessing over the things that could have done to keep a job after being fired, we find appreciation for the opportunity to find a new job more aligned with our life’s purpose. For a silver medalist, it’s the reminder that just being at the Olympics is a gift (and placing better than all but one participant is a tremendous honor!).

Even if life’s murkiest situations, gratitude can always be found. My teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, offers the simple aphorism, “No Mud, No Lotus.” From the depths of the darkness, there is always possibility for a ray of light to shine through. That car accident we caused? Maybe it’s a reminder to be more mindful while driving next time. Finding gratitude amidst challenge is certainly not easy, and our brain’s hard-wiring makes it such that this is not our default reaction in situations where we feel let down. Hence, why I mentioned gratitude as a practice earlier. The more we actively cultivate gratitude – whether consciously as a response to a disappointing event, or through daily rituals like gratitude journals, Facebook gratitude challenges, etc. – the more engrained it becomes. We truly begin to re-wire our brains and tip the scale of our reactions to come from this place.

I’m a true believer that contentment and happiness are the natural outcomes from practicing gratitude. When we are able to accept what is, and appreciate it, we stop “arguing with reality,” as Byron Katie puts it. The more we are friendly with reality exactly as it unfolds, the more content we are. It really is that simple.

Rooted in a place of gratitude, we have greater resistance to getting caught up in the thoughts of the comparing mind. Our predilections towards envy are so strong that it is considered one of the five kleshas (poisons) of Mahayana Buddhism, and is one of the key obstacles that keeps us from experiencing happiness in any given moment. When we truly are grateful, there is no need to compare our performances, bodies, incomes, etc. to those of the people around us. They are ultimately inconsequential when we come to rest amidst the innumerable blessings of our own lives.

It's unfortunate that the Olympics (like many other aspects of life) directly feed our patterns of comparing and ranking. If you find yourself in a situation (in a sport, at work, etc.) where your performance is ranked, take this information for what it is – but don’t let it define who you are, or take it as an indicator of what you might possibly contribute to the world. And if you find yourself as #2, don't try harder simply for the sake of becoming #1, or get wrapped up in what you could have done differently to be on top. Act sincerely and always give your best, without attachment to outcomes. To do this, whatever the circumstance, is always a gold-medal finish in my book.